For a while now, I’ve obviously been obsessed with the fact that disproportionate shares of Georgians seem to be stuck at the bottom of the national pile for various economic metrics, starting with per capita income (PCI). In my last post, I homed in on a comparison between Georgia and North Carolina and the fact that the Tar Heel state seems to be doing a better job of keeping its citizens out of the bottom quartile for PCI. I also wrote that I planned to write follow-up pieces looking at whether that same pattern held with other important measures.

Today we’ll take a quick look at educational achievement and — spoiler alert — the same pattern does indeed hold. Working with educational achievement data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and aggregated in an easy-to-use format by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS), I’ve found that — as with PCI — Georgia is over-represented nationally in the bottom national quartile and that we’re being significantly outperformed by North Carolina.

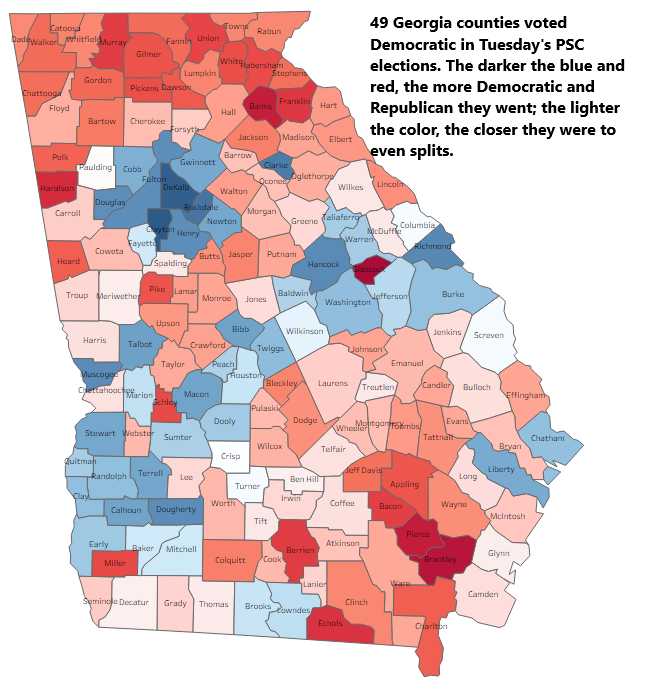

What’s more (and this is totally unsurprising), the picture that emerges when you map the latest educational achievement data is very similar to the map for the latest PCI data, both shown here. You can think of these as the results of medical imaging tests showing that a virulent socioeconomic cancer has metastasized across much of south and east-central Georgia.

I’m basing these education findings on my latest calculations for my Trouble in God’s Country Educational Attainment Index, the equation for which I’ve explained here. As with PCI and other national datasets, I rank every county in the nation for which the government has data and then break the dataset (usually a little over 3,100 counties) into quartiles. I’ve known since I started this work that there were big gaps between Metro Atlanta and most of rural Georgia, but I’ve been a little surprised at the degree to which huge chunks of Georgia’s geography and population appear to be mired at the bottom of various national piles.

In 2020, Georgia literally had more people and counties in the bottom national quartile for per capita income than any other state in the nation, including much-larger Texas and Florida. North Carolina, with basically the same population as Georgia, had a much smaller portion of its population in the bottom quartile: 16.8 percent to Georgia’s 28.5 percent. The pattern with PCI was that North Carolina has somehow done a better job of minimizing the share of its population in that bottom quartile; it might not do much better than Georgia in the top quartile, but it’s fatter through the middle ranks.

The pattern is similar with educational attainment data — although you could be forgiven for missing that fact if you simply glanced at the topline, statewide numbers shown in the table at the left. With nearly identical adult populations, Georgia has more high school dropouts and adults who only earned high school diplomas while North Carolina has more adults who got at least “some college” education; the two states had nearly identical numbers of four-year college graduates. Run all those numbers through my TIGC Educational Attainment Index equation and North Carolina scores 174.9 and ranks 29th nationally while Georgia comes in 35th with a TIGC EA Index of 170.5.

But that’s not the biggest difference. The biggest difference doesn’t come into focus until you look at how those various chunks of the adult population are divvied up and where they reside — and at how that picture has evolved over the decades. The table just below shows how the numbers have changed over the past half-century. In 1970, according to Census data, 63 of North Carolina’s 100 counties fell into the bottom national quartile and were home to 42.9 percent of its adult population; the same was true of 127 of Georgia’s 159 counties and 39.1 percent of its adults.

Over time, both states made progress. They each whittled away at the number of counties in the bottom national quartile and, for the most part, steadily reduced the share of their adult populations living in those counties. But North Carolina has clearly done better. As of the latest batch of American Community Survey data from the Census Bureau — for the years 2017-21 — North Carolina had only 24 of its 100 counties and 575,042 of its 7.08 million adults living in bottom quartile counties. For Georgia, the numbers were 86 of its 159 counties and 1.07 million of its nearly identical adult population in the bottom national quartile.

This picture is similar to the one I found in my earlier analysis of per capita income (PCI) data. In 2020, 107 counties that were home to 3.45 million Georgians were in the bottom national quartile; the same was true of 29 North Carolina counties with 1.29 million residents.

Also worth noting: In 2020, Georgia had more people living in bottom national quartile counties for PCI than any other state in the nation, including Texas. For educational attainment, we come in third nationally in this unhappy ranking, behind only Texas and California, with three and four times our population, respectively. What’s more, the only states with higher percentages of their adult populations stuck in bottom national quartile counties are Southern neighbors: Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee, plus West Virginia.

Now, there are some bottom-line questions to all this data that I can’t fully answer yet. The most of obvious of these is whether or not these differences are significant? Does it matter that so much more of Georgia’s poorest and least educated citizenry is concentrated overwhelmingly in a huge chunk of largely contiguous counties that sprawl across the middle and southern parts of the state and along its eastern border? Is it to North Carolina’s benefit that it now has less of its geography and population mired in the nation’s bottom ranks? And that those counties and people are dispersed among a handful of areas rather than being largely connected and covering more than half the state?

My working hunch is that the answer to all those questions is yes, but I’ve got some more work to do to demonstrate why and how that’s the case — and to put some numbers to those answers.

Watch this space.

Leave a Reply